Artificial Intelligence Developers must collaborate with various stakeholders to shape AI to help education systems prepare for the transformation of the world of work and society.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning bring transformational promises for education and learning. Amid SARS-COVID-19 pandemic, students and teachers around the world have relied on technology to enable distance learning. While there have been meaningful benefits, there is a greater opportunity to benefit from an AI-powered education system.

Helsinki Vocational College is exploring AI and machine-learning solutions to facilitate learning and teaching. AI-based Learning Analytics (LA) can support students individualized learning processes and contribute to the development of new pedagogical methods. In addition, Learning Analytics can support the completion of studies through automated notifications leveraging predictive models to identify as early as possible the circumstances and the phase of learning when students will most likely need support. LA provide greater insights for teachers into student’s development of competencies, well-being, and learning outcomes.

These opportunities also present potential risks. The use of data, coupled with explanatory and predictive modelling of human behavior is an inherently complex pursuit, and any use of AI carries significant ethical, legal, and social impacts.

Human rights and ethics for governance of Public Sector artificial intelligence

The challenges posed by AI in education not only raise ethical concerns but also present human rights implications. Algorithmic biases in LA can perpetuate systemic biases and maintain an unjust status quo, inadvertently exacerbating existing inequalities in education (Wise, Sarmiento, & Boothe Jr., 2021, p. 639), which can impact students’ right to non-discrimination and children’s right to equal opportunities to education. Additionally, individual students as data subjects may not be able to influence automated decision-making (Gedrimiene, Silvola, Pursiainen, Rusanen, & Muukkonen, 2020), which undermines the principle of the best interest of children and young people.

In this sense, there is an urgent need for governments to develop rigorous trustworthy AI standards and regulatory measures, grounded in international human rights law, which when combined with soft-law and ethical standards can offer effective guidance and actionable instruments to shape responsible AI development in the public sector.

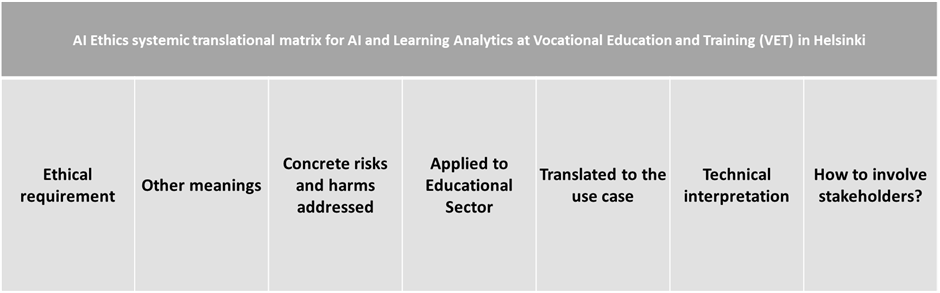

Considering these challenges, we developed a governance framework called AI Ethics Systemic Translational Matrix for AI and Learning Analytics in Education, which is a framework for multilevel translation of the EC High-Level Expert Group on AI (2019)’s seven key requirements which AI systems should meet in order to be deemed trustworthy. The model involves a pragmatic adaptation of high-level principles and guidelines and interpretation of existing laws and regulation into actionable approaches and technical measures. We focused on a Human rights-based approach (HRBA) to ethical governance of AI. A summary of our findings is described below, while the complete version was published as Open Source on the Berkman Klein Center’s website.

The framework is descried as a matrix composed of seven rows, one for each ethical requirement (Human agency and oversight; Technical robustness and safety; Privacy and data governance; Transparency; Diversity, non-discrimination, and fairness; Societal and environmental wellbeing, and Accountability), and seven columns. Each column represents one level of applied translation, using a top-down approach, starting from the high-level ethical requirements, through the identification of the human rights impacted, concrete societal risks and harms addressed, towards the technical interpretation and stakeholders’ participation methods.

Young people and Responsible AI for Education

Part of the theoretical framework abovementioned focuses on the use of AI in education and, more specifically, on the best interest of students as users of technology. Building on existing literature (Vincent-Lancrin & R. van der Vlies, 2020; Slade, Prinsloo, & Khalil, 2019; Holmes, Zhang, Miao, & Huang, 2021), we make the claim that reaching the full potential of AI in education will require that policy makers, educators and other stakeholders trust AI systems and their social use. Particular attention should be given to young people’s trust in the technology and their agency in the governance of AI, especially if AI is used for any kind of automated decision-making.

Trust in AI has multiple dimensions. In education, AI might be considered trustworthy when it does properly what it is supposed to do, but also when one can trust that human beings will use it in a fair and appropriate way (Vincent-Lancrin & R. van der Vlies, 2020). Additionally, Students should be involved to determine which data can be collected, how that data can be used, who is able to access it, and for what purposes (Slade et al., 2019). Consequently, we argue that students should have an ability to review and annotate one’s data. This feedback loop should have a significant role in AI-systems when using AI in education.

Authors:

Bruna de Castro e Silva, Doctoral Researcher, ALL-YOUTH project, Subproject 4: Resolving Legal Obstacles.

Pasi Silander, Head of ICT Development Programs in City of Helsinki Education Division (pasi.silander@hel.fi).

References

Gedrimiene, E., Silvola, A., Pursiainen, J., Rusanen, J., & Muukkonen, H. (2020). Learning Analytics in Education: Literature Review and Case Examples From Vocational Education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(7), 1105–1119. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1649718

High-Level Expert Group on AI (2019). Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI. European Commission.

Holmes, W., Zhang, H., Miao, F., & Huang, R. (2021). AI and Education: Guidance for Policy-Makers. UNESCO. Retrieved from https://www.gcedclearinghouse.org/sites/default/files/resources/210289eng.pdf

Slade, S., Prinsloo, P., & Khalil, M. (2019). Learning analytics at the intersections of student trust, disclosure and benefit. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Learning Analytics & Knowledge (pp. 235–244). New York, NY, USA: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3303772.3303796

Vincent-Lancrin, S., & R. van der Vlies (2020). Trustworthy artificial intelligence (AI) in education: Promises and challenges (OECD Education Working Papers No. 218). Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/a6c90fa9-en

Wise, A. F., Sarmiento, J. P., & Boothe Jr., M. (2021). Subversive Learning Analytics. In M. Scheffel, N. Dowell, S. Joksimovic, & G. Siemens (Eds.), LAK21: 11th International Learning Analytics and Knowledge Conference (pp. 639–645). New York, NY, USA: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3448139.3448210

Note: This Blog post is a summary of the work developed by the authors at the Summer 2021 AI Policy Clinic Sprint, hosted by the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University, in collaboration with the Education Division of the City of Helsinki, their partner, Saidot, and the Global Network of Internet & Society Centers. The complete outcomes and deliverables of the project can be found as Open Access Resources for AI in Schools at https://cyber.harvard.edu/story/2021-09/open-access-resources-ai-schools.