Tessa Whitehouse, Tampere University & Queen Mary, University of London

https://doi.org/10.58077/VYNP-9M52

The use of GIS tools in everyday life (in-vehicle satellite navigation systems, smartphone-accessed map applications) and the availability of free digital mapping platforms (such as open streetmap) mean that mapping is flourishing as a practice of everyday life and an academic endeavour. Local councils use maps to solicit residents’ views on new traffic schemes[1], Google tells Android smartphone users where they have been each month and offers photographic highlights alongside statistics about kilometres travelled and the number of cities visited, and historical organisations invite people to share collections of places that emerge from special interests and family history via platforms like Layers of London[2]. In all these examples, contemporary agencies seek to record and place experiences. What, then, are the affordances of digital mapping technologies for investigating histories of experience? Can mapping stand alone, or must it be used in conjunction with traditional scholarly methods?

What is experience?

The new history of experience ‘see[s] experiences and emotions as a mediating sphere in which the different impulses … mold into meanings, concepts, actions, and practices’.[3] As Sari Katajala-Peltomaa and Raisa Maria Toivo have said, ‘ “Experience” is invariably situationally bound; it is not a self-defining collection of anecdotal “evidence”, nor anything universal or ahistorical.’[4] These situations in which experiences occur are in large part determined by structures outside the individual. When thinking of the role of the state, for instance, we can consider ‘the multiple levels at which governing authority operates, processes of internal and external boundary formation, and how the “rule of difference” operates’.[5] This includes physical boundaries of building and street, jurisdictional ones of parish or city, and attempts to control the use of space such as regulations determining where religious meeting houses could be built. By mapping these sites and boundaries we may be able to ‘bridge the gap between macro-level changes and micro-level quotidian life’, for example by visualising patterns of building in certain areas over time.[6]

What is mapping?

In one sense, mapping is a practical process with a defined end in view: when we map, we produce an object that can be used by others. Mapping is also evaluative and reflective because of the decisions about parameters taken at the outset and because of the patterns (or lack of pattern) the completed map reveals. Closely intertwined with the everyday practice of walking, mapping invites amateur engagement and creative methods as well as technical processes and bureaucratic purposes.[7] The transformation of a map that was originally produced using triangulation and drawn on paper to the digital environment of a map created using GIS satellite systems is a specialist process.[8] Some technical skills are required to transpose historical data onto a digital map in the form of pins, information labels or images. These skills are not often taught to humanities postgraduates or researchers and in any case, there is no single method for making a map just as there is no single area of research that mapping opens to interpretation. Due to all these factors, mapping is almost always a collaborative form of research. An outline of its stages may be useful here.

How do we map?

Researchers with a particular place or phenomenon in mind may wish to begin with a map that has already been georeferenced so that they can relatively easily publish the results of their mapping online. The next stage, in the case of a map of people, places or events, is to devise a data model which captures the variables they wish to record. This will usually be an iterative process requiring several samples to which the data categories are applied and then refined. The sources used to create the map can, in some cases, be displayed on the map itself[9] and doing so makes visible the layered and scalar approach necessary in mapping projects. For example, floorplans, pictures of buildings, records of financial affairs, records of people in and out can be fitted together to produce richly detailed pictures of sites and then suggest what it was to experience those sites.

Why do we map?

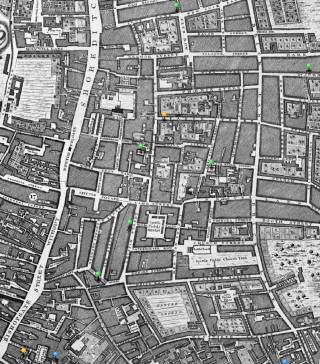

Mapping can enhance the present-day visibility of past minority communities[10]. Mapping can also highlight the complexity of interactions among and between groups, and between them and the state: from this map we note how Huguenot, Quaker, and Baptist churches cluster where there are no Anglican churches, and that Christchurch Spitalfields, commissioned in 1714 and consecrated in 1729 is an intentionally eye-catching statement of establishment dominance over the urban landscape in an area with a large number of meeting places for religious minorities.

Its spire is visible from almost every street, yard, and window in the area. Making such observations easy to see helps to move the scholarly gaze away from the traditional sites of historical attention (such as the architecture of Nicholas Hawksmoor manifested in a building that has stood, serving a single purpose, for over two centuries) to messier configurations of faith and charity, and the passing on of buildings from one group to another.

As this example suggests, investigating the history of experience at different scales (city, borough, parish, street, building) is enabled by mapping and thus understanding mapping itself as a flexible methodology can help us overcome the difficulty often faced by historians of uneven distribution of sources, incomplete records, concerns about bias and so on.

What can mapping tell us about the history of experience?

By providing snapshots of places at a particular moment we can start to map movement or patterns over time. A map can show us where communities of experience cluster (adjacency) and the onward trajectories for those communities; a map can thereby record mobility as well as emplacement and highlight potential locations of tension while ‘countermapping’ processes can record alternate histories from the perspective of participants.[11] By combining scales from the object in the room outwards, we can generate insights into the meanings people in the past found in their surroundings. Using GIS maps as a ‘base layer on which to build public history experiences’, we may also be able to ‘experientialize’ these spaces in the present for members of the public who would like to learn about those people and their world.[12] The technical requirements of digital mapping raise potential issues for the stability and sustainability of research tools and dissemination platforms especially if working with commercial partners; however, if we do not follow these paths then the usability of the tools we produce is limited. In an intellectual regime that prioritizes spinning out novel intellectual concepts for institutional and personal financial gain, it may well be in the interests of historians of experience to develop workflows that can be commodified. Unsettling though this prospect may be, historians making maps have been among the first to seek out intellectually-led but commercially-enabled ways of making their research public.[13] These prototypes are exciting; the challenge is to ensure that such future modes of scholarship remain ethical.

Notes

[1] For example, see Newham Council West Ham Park Low Traffic Neighbourhood map.

[2] See Layers of London.

[3] Ville Kivimäki, Sami Suodenjoki, Tanja Vahtikari, Lived Nation as the History of Experiences and Emotions in Finland, 1800-2000 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), 6.

[4] Sari Katajala-Peltomaa and Raisa Maria Toivo, ‘Three Levels of Experience’, Digital Handbook of the History of Experience (2022).

[5] Kimberly J. Morgan and Ann Shola Orloff, The Many Hands of the State: Theorizing Political and Social Control (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 3. See also Carl-Gösta Ojala and Jonas Monié Nordin, ‘Mapping Land and People in the North: Early Modern Colonial Expansion, Exploitation, and Knowledge’, Scandinavian Studies 91 (2019), 98-133 esp. 100-02 and 125-126.

[6] Johanna Annola, Hanna Lindberg and Pirjo Markkola, Lived Institutions as History of Experience (Palgrave Macmillan, 2024), 6.

[7] Michel de Certeau notes that ‘mastery of the social environment’ comes from ‘the practical, everyday use of … space’ in The Practice of Everyday Life (1974; second English translation 1998), 11. See also the work of Iain Sinclair.

[8] For a detailed account of how this was done for a map of London, see Locating London’s Past, ‘Mapping Methodology’, based on the work of Peter Roxloh.

[9] Such as Sites of Suffrage Memory.

[10] For example, see the map of Huguenots and Dissenters in London, 1730.

[11] See Pride of Place: England’s LBGTQ Heritage for an example and Carl Fraser’s website Countermapping for definitions and further examples of countermapping.

[12] David Rosenthal, ‘Revisioning the City: Public History and Locative Digital Media’, in Hidden Cities: Urban Space, Geolocated Apps and Public History in Early Modern Europe eds Fabrizio Nevola, David Rosenthal and Nicholas Terpstra. London: Routledge, 21-38; Tero Mustonen and Kaisu Mustonen (eds), Eastern Sámi Altas provides examples of PGIS (participatory geographic information systems) maps produced with Eastern Sámi co-researchers through the Snowchange Co-Operative.

[13] See the HistoryCity suite of apps available online and via Apple Maps.