Sari Katajala-Peltomaa and Raisa Maria Toivo, Tampere University

https://doi.org/10.58077/8F3Q-5P34

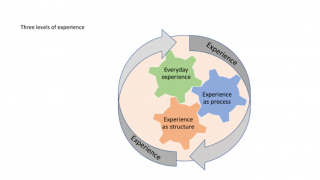

‘Experience’[1] as a word has and has had various meanings in both analytical and everyday usage. The word originates from classical Latin where ‘experientia’ meant a trial or proof; knowledge acquired through repeated trials. Similarly, the earliest medieval meaning of ‘experience’ referred to an event, the action of putting something to the test. English makes no conceptual distinction between mediated, socially shared experience and ‘lived’ experience (simple, immediate encounters with the world), in contrast to some other languages (for example German ‘Ehrfahrung’ and ‘Erlebnis’).[2] Analytically, experience can be defined in many ways, but definitions often include aspects of three dimensions or levels of analysis. Experience encompasses: 1) ways of encountering the world; 2) the simultaneous relational, intersubjective making sense of those encounters, gathering them to form knowledge, and testing one’s understanding of them against one’s own and other people’s existing explanations and 3) the influence of this sense-making or knowledge on the ‘real’ world and what people think there is to be encountered. Hence, experience becomes a social structure, determining how people deal with their world, including its cultural structures, like the transcendent, and its material surroundings, like climate.

‘Lived experience’ is a recurring expression in the scholarly literature.[3] Lived histories often emphasize the differences between ‘how things should have been’ and ‘how they really were’ in a specific historical society. ‘Lived’ emphasizes the discrepancy between norms and ideals on the one hand, and the mundane realities of everyday life on the other. In its everyday meaning, experience usually concentrates on the individual subject(s) who supposedly do(es) the experiencing. These ‘daily encounters’ can be understood as the first level of experience in analytical usage, even if the ‘authenticity’ and ‘immediacy’ of these experiences have been questioned by other scholars, like Joan Scott.[4] Feminist, postcolonial and ‘new social history’ historiography[5] argued that individual subjective experiences were, ultimately, little more than coincidental, chance stories, and their value as evidence suffered if they were not properly scrutinized in terms of their representativity as well as the nature, context, convention and origin of the production of these stories in the source materials.

‘Experience’ is invariably situationally bound; it is not a self-defining collection of anecdotal ‘evidence’, nor anything universal or ahistorical. Past experiences are mediated to us via historical sources, and as historians we also need to position ourselves within the field of historical studies using these sources.[6] Furthermore, experience is not only an immediate encounter with or observation of the world; most often, a more or less deliberate effort is made to gather these observations or encounters, and to explain them in ways that fit not only the worldviews of those doing the encountering, but also those of the people around them, their communities, societies and cultures.[7] Therefore, experience can also be seen as a social process. This ‘second level of experience’ highlights that the ways experience was produced, mediated, shared and approved or disapproved of in communities with the help of verbal or other kinds of language or modes of communication. Attention shifts from the experiencing subject to the social relationships and interdependencies in which experience is produced.

A third level of investigation is also implied in the dictionary meanings of experience, but it is even more clearly a methodological tool or category of the researcher’s making as the processes of experience are repeated often enough by a significant number of people and communities, they come to form social structures that people learn to expect, count on and despair of. The ‘structure’, however, can also be something less concrete, potentially ranging from institutions to social and cultural categories, like the transcendent. Experiences as social structures have a temporal aspect: they are formed on the basis of shared memories of past experiences, and they shape both present interpretations of the world and the future expectations of individuals and entire societies.[8]

The premise, in studying experiences as shared social processes or as structures, is that experience is born within inter-subjectivity, not in unique subjective authenticity or immediacy and then ‘contaminated’ by tradition and conventions. To focus on intersubjectivity means a heightened focus on scripts, conventions, cultural models and modes within the analysis. Focusing on the processes of the negotiation and mediation of experience also implies a focus on exactly these questions in the production and nature of the source material itself. This means the experience is not (only) about what is immediate to an individual; the focus on the shared and mediated, negotiated, or coerced in the experience itself renders the resulting observations more representative of a certain culture. The social relationships, constraints and structures shape experience; they are shaped in the history of experience.

Approaching experience on these three levels of occurrence/event, process and structurization enables the connection of micro and macro levels in historical observation, investigation and explanation, and bridges the gap between empirics or source material and theory or explanation and generalization. Since experience is both action and an analytical category, it can be used to study the forms of action and interaction that eventually create both the individual self and the community. However, as a contextual and situational phenomenon and approach, experience must always be a genuinely open question throughout time and space. For a societal history perspective, experience is a major connecting mechanism, and a process of meaning-making by the individual and the community, between past and future. This procedure of giving meaning transforms ‘everyday experiences’ into socially shared processes and sanctioned societal structures.

Notes

[1] This article is based on our previous collaboration (Sari Katajala-Peltomaa and Raisa Maria Toivo, ‘Introduction: Religion as Historical Experience,’ in Histories of Experience in the World of Lived Religion, eds. Sari Katajala-Peltomaa & Raisa Maria Toivo (Palgrave McMillan, 2022), 1–35) where more detailed analysis of ‘Three levels of experience’ can be found.

[2] Peter L. Berger & Thomas Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge (New York: Doubleday, 1966). For the impetus, theory, and results of the German Erfahrugsgeschichte on war and society, see especially Nicholaus Buschmann and Carl Horst, eds. Die Erfahrung des Krieges: Erfahrungsgeschichtliche Perspektiven von der Französischen Revolution bis zum Zweiten Weltkrieg (Paderborn: Schöningh, 2001) and Georg Schild and Anton Schindling, eds. Kriegserfahrungen – Krieg und Gesellschaft in der Neuzeit: Neue Horizonte der Forschung (Paderborn: Schöningh, 2009). See also Ville Kivimäki, Sami Suodenjoki & Tanja Vahtikari, ‘Lived Nation: Histories of Experience and Emotion in Understanding Nationalism’, Lived Nation and the History of Experiences and Emotions in Finland 1800-2000, eds. Ville Kivimäki, Sami Suodenjoki and Tanja Vahtikari (London: Palgrave 2021). Ville Kivimäki, Battled Nerves. Finnish Soldiers’ War Experience, Trauma, and Military Psychiatry, 1941–44. Åbo Academi University 2013, 52–59. On historical theory, see David Carr, Experience and History: Phenomenological Perspectives on the Historical World (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[3] E.g. Robert Orsi, ‘Is the Study of Lived Religion Irrelevant to the World We Live in?’, Special Presidential Plenary Address, Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, Salt Lake City, November 2, 2002. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42: 2 (2003): 169–74; Nancy Ammerman, ‘Finding Religion in Everyday Life,’ Sociology of Religion 75:2 (2014): 189–207.

[4] Joan Scott, ‘The Evidence of Experience’, Critical Inquiry 17:4 (1991): 773–97; Gareth Stedman Jones, ‘Une autre histoire sociale?, Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 53:2 (1998): 383–94; Martin Jay, Songs of Experience (Berkeley, CA: California University Press, 2005). For this discussion, see Rob Boddice and Mark Smith. Emotion, Sense, Experience (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 18–22.

[5] Bernard Lepedit, Les forms de l’experience: Une autre histoire sociale (Paris: Albin Michel, 1995). On the anthropology of experience, all articles in Victor Turner and Edward Bruner, eds. The Anthropology of Experience (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1986). Pertti Haapala & Pirjo Markkola, ‘Se toinen (ja toisten) historia,’ Historiallinen Aikakauskirja 115: 4 (2017): 403–416.

[6] Katie Barclay, ‘New Materialism and the New History of Emotions’, Emotions: History, Culture, Society 1:1 (2017): 161–83.

[7] Reinhart Koselleck, ‘Der Einfluß der beiden Weltkriege auf das soziale Bewußtsein’, Der Krieg des kleinen Mannes: Eine Militärgeschichte von unten, ed. Wolfram Wette (München: Piper, 1992), esp. 324–32; Jussi Backman, ‘Äärellisyyden kohtaaminen: kokemuksen filosofista käsitehistoriaa’, Kokemuksen tutkimus VI: Kokemuksen käsite ja käyttö, ed. Jarkko Toikkanen and Ira A. Virtanen (Rovaniemi: Lapland University Press, 2018), esp. 26–27; Jarkko Toikkanen, ‘Välineen käsite ja välinemääräisyys 2010-luvulla’, Media & viestintä 40: 3–4 (2017): 69–76; Jarkko Toikkanen and Ira A. Virtanen, ‘Kokemuksen käsitteen ja käytön jäljillä’, Kokemuksen tutkimus VI: Kokemuksen käsite ja käyttö, eds. Jarkko Toikkanen & Ira A. Virtanen (Rovaniemi: Lapland University Press, 2018).

[8] Reinhart Koselleck, Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time, trans. Keith Tribe (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004) [German original 1979].