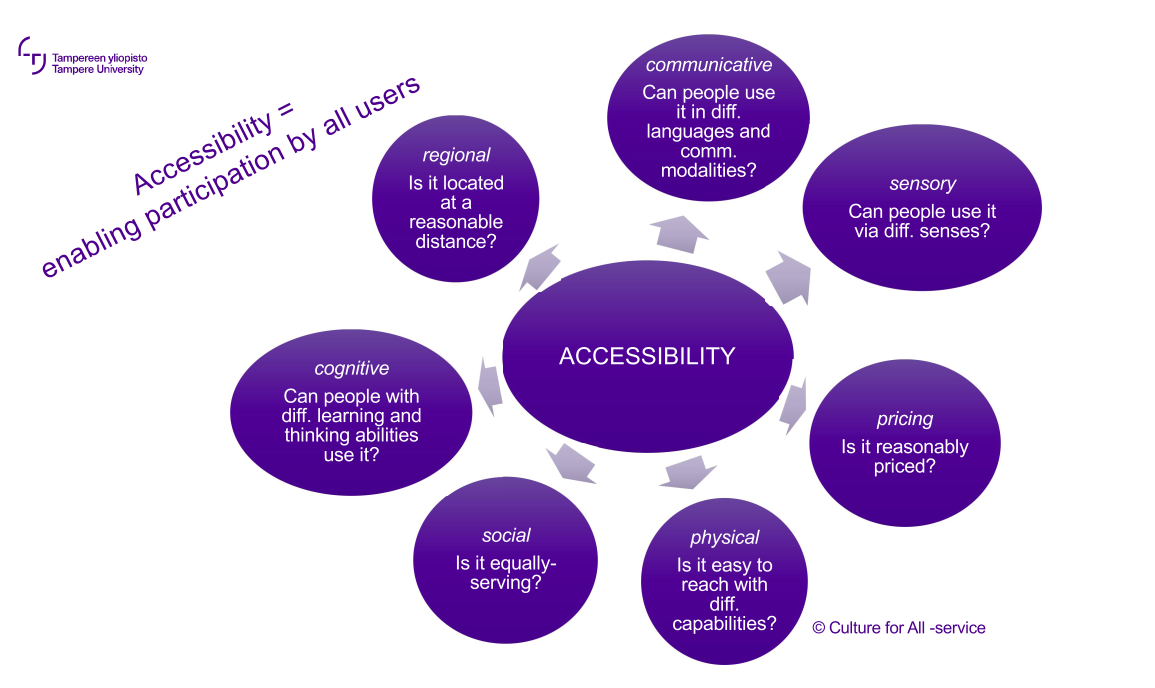

Figure from Maija Hirvonen’s presentation “Using User Potential in Accessibility: Shared Cognition in Interaction” given in Tampere, Finland on November 8, 2019.

This illuminating chart was included in Maija Hirvonen’s presentation on the fourth lecture. In it, accessibility is defined as ‘enabling participation by all users’. It is a good, comprehensive definition, but when this idea is taken into the real world and applied to public services, culture, and all other fields of life, it is not surprising that executing “design for all” is not at all easy.

Sometimes, it may even be unfeasible. However, if we ever want to achieve a just society that offers the same opportunities and the same rights for everyone, accessibility is at the very core of that task. It is not the only requisite, but it is a crucial component of true equality. Here are a few examples and thoughts on different types of accessibility.

Regional accessibility

A regionally accessible service is located at a reasonable distance from the user. An example that comes to mind is public services in small towns like the one where I am from. In past years, many services like the local police station have closed, and many others have had their opening hours cut back.

It has resulted in, frankly, quite ridiculous situations where some services are only open e.g. on the first Wednesday of each month. This can be especially tricky for elderly people—both if you have to travel more than 50 kilometers to the nearest bigger town for a service or if you need to remember complicated schedules.

Shortcomings in regional accessibility can also be dangerous. For example, if you call the police in my hometown, it takes them about 45 minutes to drive there.

This sometimes leads to absurd situations as well: the police once called me on a Friday night because my neighbors had complained that I was having a noisy party (even though it actually was my downstairs neighbor who was partying.) They did not want to take the drive in vain, so they attempted to solve the matter via telephone.

When it was not me who was making the noise, they asked me for the downstairs neighbor’s phone number. I did not have it since I barely knew him. That particular situation was just ludicrous (although some credit may be due for creative problem-solving,) but what if the complaint had been about domestic abuse or something else equally serious?

Communicative accessibility

Communicative accessibility means availability in different languages and communication modalities. Presumably, the digitalization of public services falls under this category—or at the very least, it is connected to this type of accessibility. Examples of this phenomenon abound in Finnish society. Bank services, mail delivery, and tax forms come to mind.

Of course, digitalization is not inherently a bad thing—actually, I am very much in favor of it, as it simplifies running many errands and is often more efficient and reliable than e.g. delivering paper mail. However, the more public services are digitalized, the more significant it becomes to assure that those services are also available in simple language and in all the languages spoken by those for whom the services are aimed—especially if the e-service is the only option available.

Sensory accessibility

Availability via different senses is the type of accessibility I am most familiar with because there is a great overlap between it and my professional field, translation, and interpretation; sensory accessibility includes i.a. audio description (AD) and speech-to-text interpretation.

For a couple of years now, I have been delving into AD especially. For instance, I am currently part of a project where we are audio describing a play by the Finnish Blind Theater Sokkelo. My bachelor’s thesis is also about AD.

AD is actually how I became acquainted with the term accessibility in the first place, although it now seems a bit surreal since accessibility discourse constantly pops up here, there, and everywhere. The field of AD is growing at mind-boggling speed. The Finnish Film Foundation now requires that all the films they help fund—that is, the vast majority of Finnish films—have to be audio described. Some pressure to improve sensory accessibility also comes from the European Union, which is a fantastic thing, although the implementation of the directives is still underway.

Accessible pricing

Simply put, ‘accessible’ pricing is reasonable. I suspect that this may be a considerable issue, since many accessibility services are currently provided by private entities, and the field, even though growing, is still nascent.

Furthermore, the people who need accessibility services the most are often in a vulnerable position, to begin with. Is someone looking after their interests on their terms?

Physical accessibility

This is another type of accessibility I am personally very familiar with. My father has been in a wheelchair for almost seven years, and I have often discussed issues of the accessibility of physical locations, like buildings, with him.

One of those conversations that have especially stuck in my mind is when he once told me that the health center in his town has a high threshold that is difficult to cross with a wheelchair. We were both baffled by such an oversight; had no one come to think that a health center is one of the most crucial places to be accessible by wheelchair?

Another example he has mentioned are roads in bad condition—they are exhausting to navigate through when you are pushing the wheelchair forward by hand.

These are things that I had never thought of from this point of view. These hindrances are not only inconvenient to people in a wheelchair, however. I would guess that perilous roads and high thresholds must be a nuisance to elderly people as well, and probably to many other groups of people too.

Social accessibility

If a service is socially accessible, it is equally easy for everyone to use it. This is connected to the concept of design for all which was discussed in the lectures. Speakers seemed to agree that such a concept is not always feasible and that when a service is designed for a certain group, the focus should be on customizing the service for their needs, not on trying to create something for everyone and risk ending up with nothing for no-one.

However, I wonder whether this principle applies to public services since they are designed for everyone. I guess the question then becomes devising multiple types of accessibility and implementing them all side-by-side.

Cognitive accessibility

Cognitively accessible services are also usable for people with different kinds of learning and mental disabilities. Web services come to mind, but instead, I would like to tell an anecdote about voting in the elections to the European Parliament (EP) this spring.

It was my first time voting in the EP elections in Tampere, so I had no idea that there were specific voting zones, assigned based on one’s current address. I was practically living at my boyfriend’s place in Kaukajärvi but I still had my own apartment—and my official address—in Kaleva.

I thought I would stop by the Kaukajärvi library to cast my vote on the morning walk with our dog. However, at the library, I found out that I would have to go to Kaleva to vote. I returned home, and a few hours later, I went to Kaleva. There, I accidentally went to the wrong place at first because the names were very similar, but on the third try, I finally managed to cast my vote.

Now, I am very passionate about politics, so I took the extra steps to cast my vote out of principle. But what if this had happened to someone else? I would think it has; I cannot be the only one who has ever experienced this. And what if that other person was mentally disabled? What if they had trouble navigating in the city, following instructions, and locating places? And that would not probably be the only stumbling block on the way. Is this kind of system truly accessible, even if the voting locations are physically accessible? Was this taken into consideration when the system was designed?

To summarize, there are many types of accessibility because there are many kinds of people with many kinds of needs. Some systems and services are meant for everyone, and many of them are vital in handling everyday life. It is not simple to design services that take into account all kinds of accessibility needs, but it is essential if we want to build truly equal societies where people are free to live their lives the way they want to live them.