In institutions of higher education, teamwork appears as a novel approach to studies. For most people, the word “team” conjures images of team sports, executive or project teams in business organizations, or quick response teams in healthcare or military. In those teams, it is self-evident that they will need to utilize different capabilities of the team members in order to succeed in complex situations they encounter. It is now becoming evident that all working life is more complex than the hierarchical industrial age organizations can easily manage. Many of those industrial age organizations need to make a shift towards more self-directed structures where people are able to work together towards shared goals, make best use of and develop their different capabilities, and are supported in doing this by their colleagues and superiors.

Self-directed, autonomous teams, however, do not just happen by themselves. They need clear and unambiguous administrative and managerial support from the whole organization, empowering organizational structures, as well as social practice arrangements (Kemmis, 2014), habits and mental models (Senge, 2006) that support self-directed collaboration. Many of the habits and mental models involved are deeply ingrained and have to do with how we see others and ourselves and what is our conception of knowledge, and the socially shared practice arrangements take even longer to shift – if they do at all. This is why anyone who wishes to facilitate self-directed teamwork needs to seriously consider his own working practices and be mindful of what he or she is trying to change or achieve. The question that needs a sincere answer is simply “What are you doing?”. The “you” in the question is both singular for each person and plural for the collective group, team or the whole community. In terms of the practice architecture (Kemmis, 2014) the question of practice projects “What are you doing?” is asking to be answered from the perspectives of ‘sayings’, ‘doings’ and ‘relatings’.

Anyone who wishes to facilitate self-directed teamwork needs to consider his own working practices and be mindful of what he or she is trying to change or achieve.

Below is one attempt to put in words what team coaches in TAMK Proakatemia, a special unit for entrepreneurship education in Tampere University of Applied Sciences are trying to do.

Principles of Team Coaching

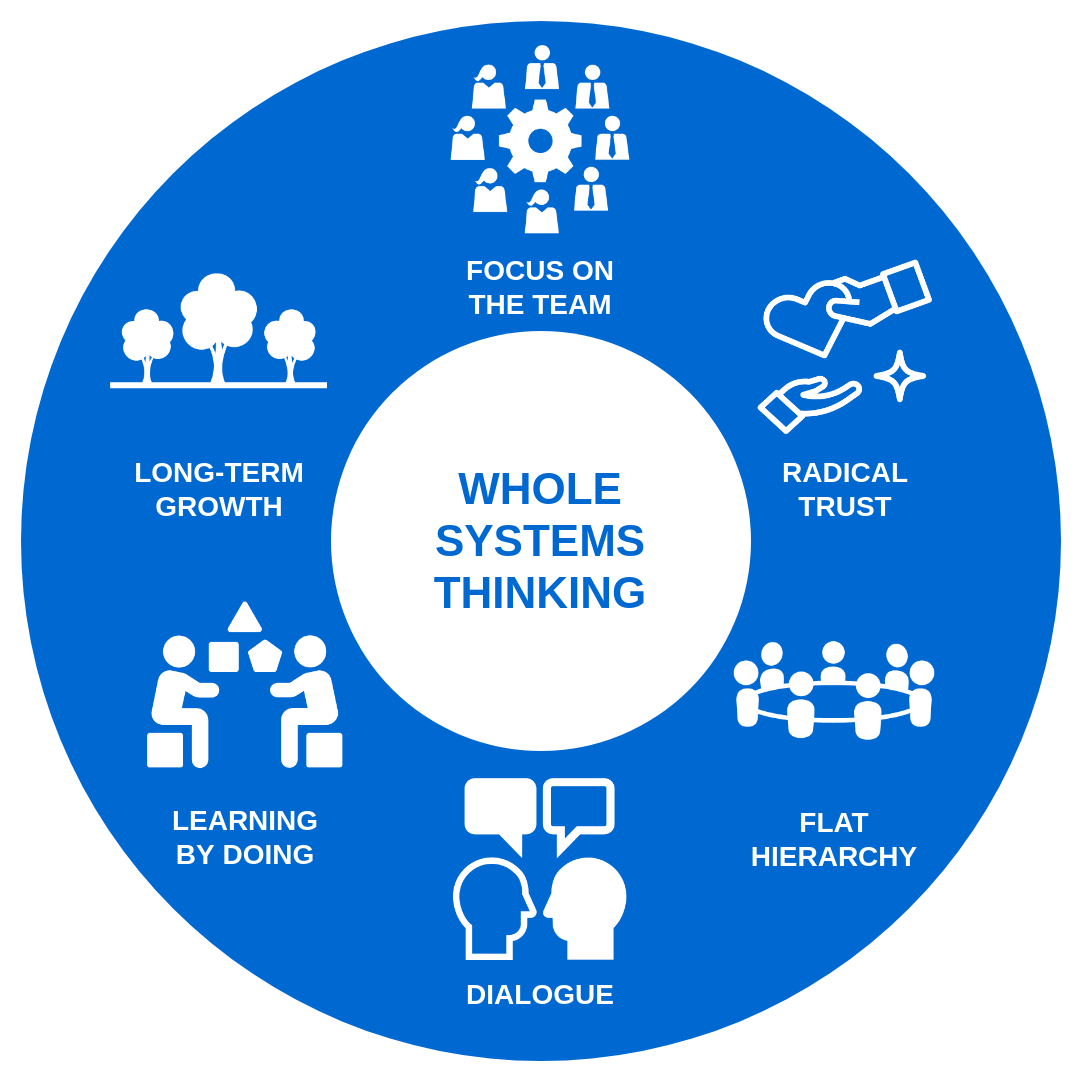

Team coaching approach in TAMK Proakatemia is based on the following principles:

- Bringing the team to the center of education.

- Building radical trust and maintaining a flat hierarchy.

- Fostering dialogue.

- Learning by doing.

- Focus on long-term growth.

- Systems thinking.

Bringing the team to the center of education, while acknowledging and treating each individual student as a unique and valued person, capable of intelligent thought and action. Bringing the team to the foreground also means acknowledging the self-centered individualism that is prevalent in the society and helping the students focus on the good of the community, the team, and the team enterprise, rather than solely on their individual wants and desires. Self-centered individualism is one of the primary reasons of the loss of meaning (Taylor, 1992) and depression (caused by what Viktor Frankl calls existential vacuum (Frankl, 2010)) experienced by young people. In order to help the students transcend their individualistic focus, a team coach has to pay close attention to how individual choices will affect the larger whole and help others to do the same.

Building radical trust and maintaining a flat hierarchy; the students are always both allowed and encouraged to take the center stage in the activities of the learning community. The power structure, even when based on (supposedly) superior knowledge or skill, should never be used as an excuse for the teachers to limit or seize the students’ opportunities to think, act or lead. In organizations, the assumed separation between thought and knowledge (leadership) and action (work), and the hierarchical structures that this separation implies are a major barrier to dialogue and learning together (Bohm, 2004; Senge, 2006).

Fostering dialogue by maintaining the context of dialogue, showing example of engaging in skilled conversation and dialogue as thinking together. This includes following the principles of genuine listening, suspending and bringing into open own assumptions, showing respect for others and their contribution to dialogue, as well as giving voice to shared thought and experience, even when it is still fragile (Isaacs, 1999). The principle of dialogue also sets requirements for the relationship between the participants; the students and teachers who wish to engage in dialogue need to recognize each other as colleagues in exploring their thinking and reality together and in creating new shared knowledge (Senge, 2006).

Learning by doing; reconnecting thought, knowledge, and action. Critical reflection and dialogue within the team in a psychologically safe environment with low interpersonal risk for the participants is essential for enabling what Chris Argyris calls double-loop learning. According to Argyris (2004), double-loop learning means “the detection and correction of errors where the correction requires changes not only in action strategies but also in the values that govern the theory-in use”. This kind of questioning of the status quo necessitates radical trust between the participants and is not possible if they are afraid of discussing errors or their root causes in the open, or, as is sometimes the case, even engaging in activities that would allow for the possibility of public mistakes or failure. Within educational contexts, focus on assessing (grading) individual performance hinders both engagement in group work where public mistakes or failure are possible, as well as open dialogue on the performance of the team and team learning.

Focus on long-term growth. While the team entrepreneur students often need to focus on managing their business in the short-term, the coach will need to maintain a long-term perspective on the development of the team and the individual students within it. This will mean, for example, treating mistakes and failures as learning opportunities, even if they are, and sometimes should be, causes for economic loss and distress for the team entrepreneur students in the short term. This is why a team coach needs to maintain a certain distance from the daily troubles of the team.

Whole systems thinking

One overarching discipline that combines all of the above principles and can help both aspiring and practicing team coaches develop their capabilities is systems thinking. Systems thinking is “a way of thinking that gives us the freedom to identify root causes of problems and see new opportunities” (Meadows & Wright, 2008). It can also be conceptualized as a conceptual framework, a body of knowledge and tools to make the patterns of whole system interactions and interrelations clearer and to help us figure out how to change them (Senge, 2006).

As one of the early developers of systems thinking, Donella Meadows writes, complex, self-organizing, nonlinear, feedback systems (like teams) are inherently unpredictable and not controllable or optimizable but they can still be designed and redesigned (Meadows & Wright, 2008). Indeed, any attempt at optimizing a complex system will likely lead to dysfunctional whole and reduced resilience! There is no certainty within complex, self-organizing systems, except that there are bound to be surprises where we can learn from if we are ready to engage in the above disciplines:

We can’t impose our will upon a system. We can listen to what the system tells us, and discover how its properties and our values can work together to bring forth something much better than could ever be produced by our will alone. (Meadows & Wright, 2008).

The concept of systems thinking, especially in the context of education, is also closely related to the shift from mechanistic idea of education and learning towards more ecological thinking (“[..] a shift of emphasis from relationships based on separation, control and manipulation towards those based on participation, empowerment and self-organization” (Sterling, 2001)). Seen through the systems lens, education can become a practice that intertwines both ecological and social sustainability.

Figure 1 Summary of core principles of team coaching

TAMK Proakatemia is a special entrepreneurship education unit in Tampere University of Applied Sciences (TAMK), which has in its core the idea of entrepreneurial team learning, a radically empowering approach to education, and team coaching. Currently, Proakatemia consists of ~150 team entrepreneur students and 11 team coaches.

References

Argyris, C. 2004. Reasons and rationalizations: The limits to organizational knowledge. Oxford University Press.

Bohm, D., & Nichol, L. 2004. On Dialogue. Routledge.

Frankl, V. E., Batthyány, A. (transl.) 2010. The Feeling of Meaninglessness: A challenge to psychotherapy and philosophy. Marquette University Press.

Isaacs, W. 1999. Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together: A Pioneering Approach to Communicating in Business and in Life. Currency.

Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Edwards-Groves, C., Hardy, I., Grootenboer, P., & Bristol, L. 2014. Praxis, Practice and Practice Architectures. In S. Kemmis, J. Wilkinson, C. Edwards-Groves, I. Hardy, P. Grootenboer, & L. Bristol, Changing Practices, Changing Education (pp. 25–41). Springer Singapore.

Meadows, D. H., & Wright, D. 2008. Thinking in systems: A primer. Chelsea Green Pub.

Senge, P. M. 2006. The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization (Revised & Updated edition). Doubleday.

Sterling, S. R. 2001. Sustainable Education: Re-visioning Learning and Change. Green Books for the Schumacher Society.

Taylor, C. 1992. The Ethics of Authenticity. Harvard University Press.

Author

Timo Nevalainen, TAMK Business, timo.nevalainen@tuni.fi

Researcher, Learning & Growth in Teams (LeGiT) research group

Team Coach, TAMK Proakatemia

Senior Lecturer, Circular And Responsible Economy (CARE)

Areas of expertise: Professional education, educational theory, team learning, dialogue, qualitative research, knowledge management

The author is a Trustee in Academy of Professional Dialogue, https://aofpd.org

Photo: University of Tampere/Jonne Renvall