Higher education institutions need Virtual Exchange (VE) in order to keep fulfilling their mission of educating students for civil and professional purposes in a globalized world. In order to find good practice examples of implementing VE, Stärke (2020) conducted case studies of three universities: DePaul University (USA), University of Potsdam (Germany) and Malmö University (Sweden). In his study Stärke focused on three success factors for the implementation of VE: culture, pedagogy and organization. Based on his research Stärke created an implementation plan of VE for Goethe University (Germany).

What is Virtual Exchange?

Virtual Exchange is a collaborative digital teaching and learning format that is integrated into a university course at two or more universities in different countries. This article introduces the structures and processes necessary for a successful implementation of Virtual Exchange in higher education. It is also referred to as Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) or Globally-Networked Learning Environments (GNLE). VE can be an instrument of Internationalization at Home and Internationalization of the Curriculum. The latter focuses on the incorporation of international, intercultural and/or global dimensions into the content of formal curricula including learning outcomes, assessment tasks and teaching methods (Leask 2015, 9). It is this last aspect of VE that we find important to consider in the curricula development especially in teacher education.

This article introduces the structures and processes necessary for a successful implementation of Virtual Exchange in higher education.

Best practices in Virtual Exchange

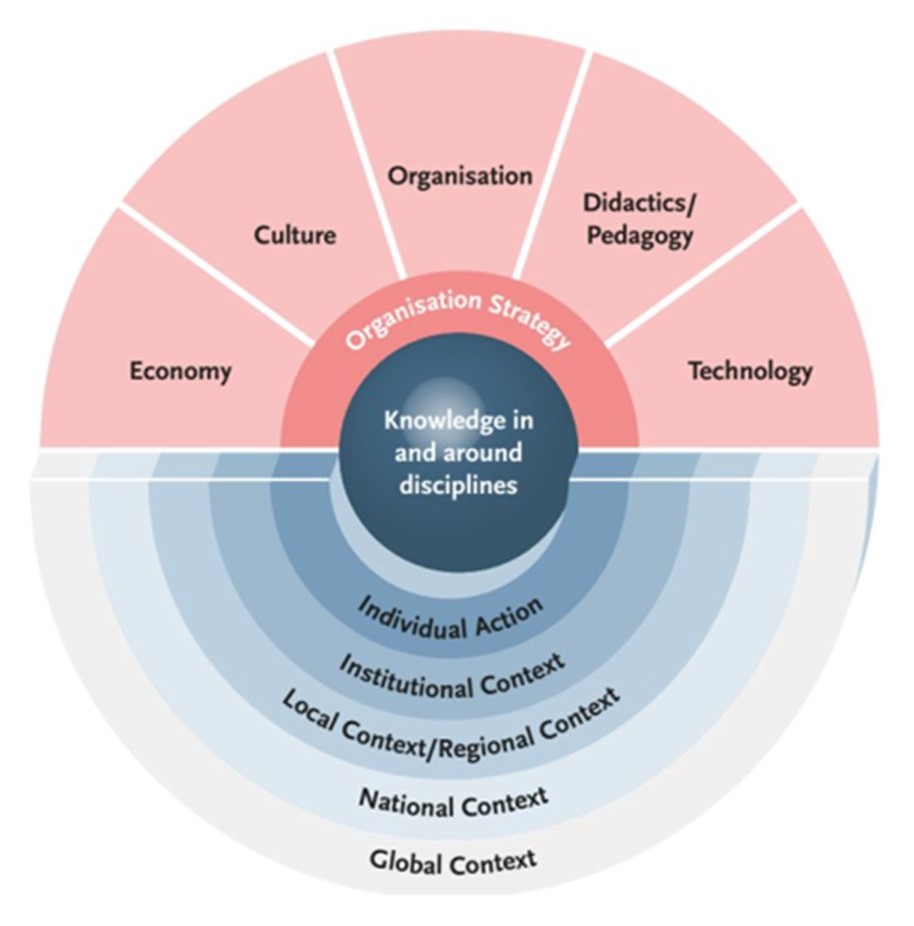

The theoretical frame of reference draws on the framework of Knoth & Kyi (2016) for sustainable internationalization that particularly pertains to VE and other digital models and formats of Internationalization of the Curriculum (figure 1).

Figure 1 Descriptive Framework for IoC and VE (Knoth & Kiy 2016, adapted from Leask 2015)

Of the five aspects, economic, cultural, organizational, pedagogical and technological, that tie into an organization strategy for IoC, the study focused on three: cultural, pedagogical and organizational aspects.

Knoth and Kiy delineate the cultural aspect as one of the success factors for establishing VE (2016). Stärke (2020) finds two dimensions of culture: one as a learning and development goal for students and academic teachers (culture as content and interaction), and another one as a situated learning structure which in the case of VE relies on how digital and social media and learning management systems are used and understood (culture as medium and structure) primarily by stakeholders like faculty, instructional designers, administrators and also students.

Culture in VE not only refers to what students and faculty realize about cultural differences or reflect upon, but also to how they learn in terms of both norms, values and collective approaches to learning as well as to learning design aspects and how digital media and learning management systems are used and conceived. Stärke concludes that the crucial determinator in fostering intercultural skills development in students is the academic teacher and their capabilities. (Stärke 2020, 73.)

Regarding the pedagogical aspect of successful VE implementation, Knoth and Kiy (2016) explicitly emphasize the role of faculty as important stakeholders and change agents. University teachers have to understand the cultures of diverse learners with different cultural backgrounds for efficient VE course design (Ahn, Yoon & Cha 2015; Gu, Wang & Mason 2017), know how to connect with their partner and to set up a VE module, have the skills to internationalize learning outcomes and assess a virtual collaboration, coach virtual teams, know about collaboration tools, and about assessing and grading with an international partner (Rubin 2017, 36).

The findings show that all three institutions studied have put a strong focus on either providing regular faculty training for VE (DePaul University, Malmö University) or communicating VE related pedagogical and didactic measures to faculty via various websites (University of Potsdam) as an avenue to educate this group of vital stakeholders.

A crucial success factor for the set-up of VE across an institution of higher learning is the organizational situation and environment as it represents the basis for analysis to develop a strategic implementation plan (Knoth & Kiy 2016, 10). Moreover, the authors state that such a plan is a component of the institutional internationalization process with key players and stakeholders for this process constituting university management, international offices and faculty (ibid.)

From the empirical data of the three cases Stärke (2020) found the following organizational structures for successful implementation of VE:

- VE coordination office

- Faculty training programme

- Seed funding programme to support individual VE project initiatives

- A selection committee / advisory board to steer seed funding programme

- VE website that increases visibility and participation

- Faculty handbook on VE pedagogy, didactics, and organization

According to Stärke (2020), supporting academic teachers is essential in order to utilize the full potential of VE. Therefore, a core structure for VE implementation constitutes a VE training programme for teaching faculty. Best practices in this context particularly focus on fostering intercultural awareness and international partnering:

- The training programme should include intercultural aspects, skills pertaining to technology (ICT skills, social media usage and e-learning tools), as well as partnering and reflection skills. A European project on VE in higher education has recently released an open source online faculty training programme that covers these components and that institutions could integrate into their implementation (EVOLVE 2020). However, it is advisable to combine online training with peer-to-peer interaction in order to deepen and expand knowledge creation among academic teachers across different disciplines. This is particularly vital given the fact that within different academic disciplines there are divergent cultures of teaching and divergent degrees of understanding intercultural interactions (Kumi-Yeboah 2018).

- Given this observation, the training programme needs to make sure that academic teachers from different disciplines receive the knowledge, skills and support necessary to establish a functional working relationship with their international colleagues that is grounded in mutual trust.

- Institutional VE training should include the raising of awareness among academic teachers about their essential role in facilitating intercultural skills in addition to academic content (ibid.).

- The university should install incentives or support instruments for faculty to meet their international colleagues face to face as a mechanism for relationship building or solidification. This, for instance, can be done by allocating grants from the Erasmus+ staff mobility programme to VE partnerships within Europe. These can be combined with or integrated into the aforementioned seed funding structure.

Closely connected to the set-up of the above presented structures are processes which are equally vital for university-wide VE preparation and implementation. These entail the involvement of university leadership to create institutional leverage, the development of a VE brand as a collaborative effort between different departments, alignment with and integration into institutional plans and policies (Jansen 2015; Rubin 2017), and lobbying VE to different key stakeholders (academic teachers, students, heads of administrative and academic departments, university executive board) (Wilson 2013; Jager et al. 2019). Finally, providing continuous support to academic teachers on instructional, pedagogical, intercultural and organizational (e.g. related to international partner selection) questions is another significant process for establishing and maintaining VE across a university.

Conclusions

Incorporating Virtual Exchange into the curriculum can be the first step in Internationalization of the Curriculum in order for students to acquire the competences required in the globalized world of work. Stärke’s findings show that teaching and facilitation in VE implementations is a demanding task. Consequently, he emphasizes the importance of a comprehensive faculty training programme. It seems obvious that internationalization of the curriculum in teacher education is of double importance regarding teacher students’ competences not only as students but also, and even more importantly, as future teachers.

References

Ahn, M.L., Yoon, H. & Cha, H. 2015. Cultural Sensitivity and Design Implications of MOOCs from Korean Learners’ Perspectives: Case Studies on edX and Coursera. Educational Technology International 16 (2), 201-29.

Gu, X., Wang, H. & Mason, J. 2017. Are They Thinking Differently: A Cross-Cultural Study on the Relationship of Thinking Styles and Emerging Roles in Computer-Supported Collaborative Online Learning. Journal of Educational Technology &Society 20 (1), 13-24.

EVOLVE. 2020. Training Resources. Read on 15.12.2020. https://evolve-erasmus.eu/training-resources/

EVOLVE Project Baseline Study. Groningen: University of Groningen. Read on 03.01.2020. https://evolve-erasmus.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Baseline-study-report-Final_Published_Incl_Survey.pdf

Jager, S., Nissen, E., Helm, F., Baroni, A. & Rousset, I. 2019. Virtual Exchange as Innovative Practice Across Europe: Awareness and Use in Higher Education

Jansen, J.R. 2015. Globally Networked Learning Environments: An Administrator’s Perspective. In Schultheis Moore, A. & Simon, S. (eds.) Globally Networked Teaching in the Humanities. New York: Routledge, 46-57.

Knoth, A. & Kiy, A. 2016. Challenges in Internationalized Teaching and Learning. Potsdam: University of Potsdam. Read on 15.12.2019. at https://www.uni-potsdam.de/fileadmin01/projects/oilup/Knoth_Kiy_COIL_final_180216.pdf

Kumi-Yeboah, A. (2018). Designing a Cross-Cultural Online Learning Framework for Online Instructors. Online Learning Journal 22 (4), 181-201.

Leask, B. 2015. Internationalizing the Curriculum. London: Routledge.

Rubin, J. 2017. Embedding Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) at Higher Education Institutions. In Casper-Hehne, H., Egron-Polak, E., Green, M.F., Matei, L., Nokkala, T. & Purser, L. (eds.) Internationalization of Higher Education. Developments in the European Higher Education Area and Worldwide. Berlin: DUZ Academic Publishers, 28-42.

Stärke, P. 2020. Implementation of Virtual Exchange at Goethe University Frankfurt: Applying Organizational, Pedagogical, and Cultural Aspects from Three Case Studies. Tampere University of Applied Sciences: Master’s thesis. Available at http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:amk-2020110222040

Wilson, M. 2013. An Inquiry into the Impact of Institutional Strategies on Faculty Partners’ Development of Globally Networked Learning Environments (GNLEs). Doctoral Dissertation. Montreal: McGill University.

Authors

Patrick Stärke,

integrated BA and MA in North American Studies from the University of Bonn, Germany,

currently a student of the MBA in Educational Leadership,

Head of International Partnerships at the International Office of Goethe University Frankfurt

Email: p.staerke@em.uni-frankfurt.de

Sisko Mällinen,

PhD, Principal Lecturer,

School of Professional Teacher Education, Tampere University of Applied Sciences

Email: sisko.mallinen@tuni.fi

Photo: Unsplash