Introduction

The evolving competence requirements of the mechanical engineering industry demand increasingly precise, safety-oriented, and systematically structured vocational education (Teknologiateollisuus ry, 2024).

Grinding as a process is a distinctive operational whole, where mistakes typically lead to economic losses—such as shortened life cycles of customer-end products—or even increased safety risks. From a learning perspective, grinding is particularly demanding as it integrates machining, measurement, and the understanding of material behavior. Examples include selecting the appropriate grinding wheel, interpreting machine sounds, performing reliable measurements, reading technical drawings and applying them to the work process, or understanding how the workpiece reacts during grinding.

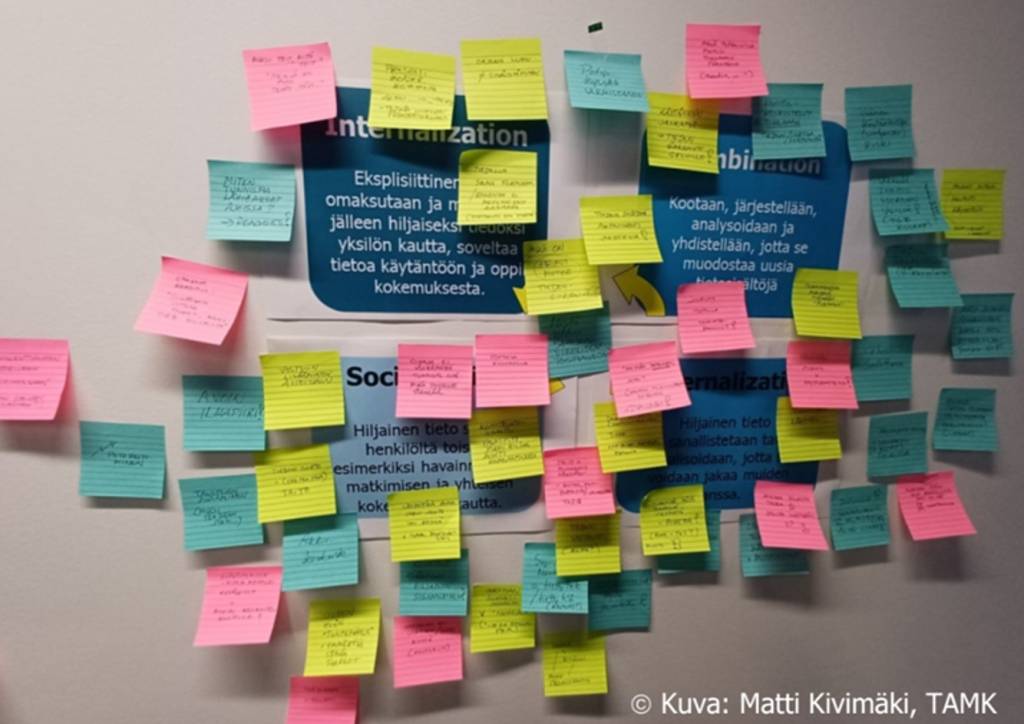

Such tacit knowledge is traditionally transmitted from experienced grinders to novices through informal interaction over extended periods, a phenomenon also observed during the Konepaja-akatemia 2.0 project (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Suhonen et al., 2025). The project team identified patterns reminiscent of knowledge transfer as described in the SECI model by Nonaka and Takeuchi (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995) (see Figure 1). The unstructured nature of this knowledge makes it difficult to incorporate into systematic training.

Figure 1 Observations gathered from SECI-themed activities during the first co-creation workshop of the Konepaja-akatemia 2.0 project (Photo: Matti Kivimäki)

In the second co-creation workshop of the Konepaja-akatemia 2.0 project (May 6, 2025, Sastamala), the aim was to respond to these challenges by developing pedagogical solutions that combine digital simulation-based learning, online learning environments, and expertise from working life. The goal of Workshop 2 was to support learning and the transfer of tacit knowledge through three parallel development themes: (1) enhancing the authenticity of the VR simulator, (2) structuring the grinding process and making embedded tacit knowledge visible, (3) evaluating the content and pedagogical structure of the Moodle-based DigiCampus learning platform (www.digicampus.fi)

Theoretical Framework

This article presents an analysis of the results of the co-creation workshop and examines their relation to selected theoretical frameworks, particularly those of authentic learning (Herrington et al., 2010), the externalization of tacit knowledge (Nonaka & Von Krogh, 2009), simulation pedagogy (Lateef, 2010; Salas et al., 2009), and the accessibility and pedagogical impact of digital learning environments (MacNeill et al., 2021).

Transforming tacit knowledge into formal learning content requires pedagogical structures that enable experience, interaction, and shared reflection. Without these, learning materials remain limited to explicit knowledge and fail to support deeper practical understanding (Lateef, 2010; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Nonaka & Von Krogh, 2009; Salas et al., 2009). In our interpretation, when explicit knowledge is combined with collective action and reflective interaction, learning does not remain merely conceptual—it also facilitates the emergence, articulation, and internalization of tacit knowledge.

The SECI model by Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) outlines four phases of knowledge conversion: socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization. Simulation-based learning provides an opportunity to externalize experiential knowledge into concrete observations, through which learners can develop their professional reasoning and skills.

Simulation pedagogy has proven effective in vocational education contexts where precision and safety are critical (Lateef, 2010; Salas et al., 2009). Its strength lies in offering repeatable, guided scenarios where learners can practice technical skills without real-world risks.

Authentic learning emphasizes the contextual relevance of tasks and environments. According to (Herrington et al., 2010), learning is most effective when it connects directly to real work-life situations or environments that simulate them. The grinding simulator aims to produce an industrial learning environment as realistic as possible. Authentic tasks and open-ended problem-solving provide a foundation for learning where knowledge is not an abstract goal but a concrete tool for action (e.g., the ability to adjust grinding parameters with justification).

From the perspective of tacit knowledge (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Nonaka & Von Krogh, 2009), learning is not limited to explicit facts or instructions. Tacit knowledge cannot simply be “transferred”; it is externalized through interaction, demonstration, side-by-side work, or metaphorical language. In practical steps such as grinding processes, this invisible knowledge forms a critical component of vocational expertise—and this is precisely where simulation practice and guided reflection can play a vital role.

Simulation alone won’t suffice—deep learning in grinding requires structured pedagogy and active transfer of tacit knowledge.

In post-pandemic education discourse, digital pedagogy has increasingly come under scrutiny. According to (MacNeill et al., 2021), the effectiveness of digital learning environments depends not only on technological features but also on how they support accessibility and connect with learners’ real-life contexts. Platforms like DigiCampus enable the creation of personalized learning paths and progress tracking, but their pedagogical value depends on intentionally designed learner-centered content and structure.

Technology is not a neutral medium—its design can either enhance or hinder learning. The grinding simulator used in this workshop is one such example of a digital learning environment, whose pedagogical value depends on how well its use connects with prior experience, guided reflection, and authentic workplace contexts.

Workshop Implementation and Analytical Approach

The second workshop of the Konepaja-akatemia 2.0 project focused on integrating simulation-based learning, online platforms, and tacit knowledge to enhance pedagogical effectiveness.

This co-creation workshop was structured around a three-station rotation model. The participants (n=17) included vocational teachers, developers, and professionals from the mechanical engineering industry. At the stations: (1) the most recent and advanced prototype of the VR simulator was tested, (2) the grinding process flowchart was evaluated interactively, and (3) the Moodle-based DigiCampus learning platform was reviewed from the learner’s perspective. Participants’ insights were collected through oral discussions, post-it notes, and Microsoft Forms.

Industry co-creation revealed how flowcharts, simulations, and digital platforms together build meaningful vocational competence.

The analysis applied a phenomenographic, interpretive approach (Fortkamp, 2000), aiming to explore the varying conceptions that participants had of the core phenomena—such as the phases of the grinding process, the pedagogical role of the VR simulator, and the structure of the Moodle platform (www.digicampus.fi). Although traditional categories of description were not systematically constructed, the approach followed a phenomenographic logic that focuses on identifying qualitatively different understandings of a shared topic.

Results

Feedback on the VR simulator was largely positive. The simulator’s visual appearance, controllability, and technical stability were considered successful. Notably, the progress in development was highlighted by the fact that the use of VR goggles no longer caused motion sickness.

However, participants also suggested improvements. These included incorporating grinding process parameters such as rotation speed and feed rate, developing a realistic sound environment, displaying material data of the grinding wheel in use, and simulating hazardous events (e.g., wheel breakage caused by excessive feed).

The simulator was primarily viewed as a safe training environment, but one that needs to be supplemented with explanatory and contextual support. This observation aligns with prior research on simulation-based learning, which emphasizes the importance of guidance, feedback, and contextual relevance for effective learning (Lateef, 2010; Salas et al., 2009).

Feedback regarding the grinding process flowchart suggested that while the structure was generally sound, some content-related aspects required refinement. Examples included: (1) the impact of preheating the machine on measurement accuracy, (2) the need to straighten the grinding workpiece, (3) individualized notation practices, (4) burr removal during finishing, and (5) how wheel selection depends on company-specific routines. A particularly valued idea was the “senior button”, a virtual support function that would assist in situations where in real life one would typically consult a more experienced colleague.

At the Moodle review station, the platform’s structure was deemed clear, but areas for improvement were noted in consistency of terminology, visual accessibility, and tracking progress through training materials. Participants expressed a desire for clearer presentation of learning objectives, reading guidelines, and modular content organization by skill level.

The “senior button” transforms silent expertise into real-time guidance, conveying lifelong knowledge from expert to novice.

In terms of learning content, the areas that were most clearly seen to support learning were occupational safety, grinding tools, and cooling methods. In contrast, the dressing process, process parameters, and the Barkhausen method drew more critical or hesitant evaluations, suggesting a need for further clarification and content development in these areas.

Discussion

The results indicate that improving grinding education requires the alignment of multiple, mutually reinforcing solutions. The simulator enables practical experimentation, the process flowchart structures the sequence of operations, and the Moodle platform provides a framework for the learning path.

The transfer of tacit knowledge does not happen automatically—it requires pedagogical scaffolding that accounts for context, sequencing, and concrete examples. Moreover, these components must form a coherent and functional whole.

The “senior button” emerged as a particularly innovative concept from the project team. It combines technical implementation with pedagogical externalization of tacit knowledge. Meanwhile, the Moodle platform requires a clearer visual structure and learner-oriented navigation to fully realize its pedagogical potential.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The workshop confirmed that developing grinding education is feasible when three key elements are combined: structured pedagogical content, a technical training environment (i.e., the grinding simulator), and workplace-derived tacit knowledge. Achieving this requires a high level of structural integration and goal-oriented development work.

Recommended next steps include:

- Implementing the senior button concept in the simulator prototype and piloting it

- Further refining the visual and structural navigation path of the Moodle-based DigiCampus platform (www.digicampus.fi)

- Documenting tacit knowledge through video and case-based formats in cooperation with industry partners

Co-creation proved to be a productive method for developing professionally meaningful, safe, and learning-supportive educational solutions.

The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT by OpenAI as a tool for linguistic refinement and structural drafting support during the article preparation. All content and interpretations are the authors’ own responsibility.

References

Fortkamp, M. B. M. (2000, January). REVIEW: Marton & Booth (1997), Learning and awareness. https://periodicos.ufsc.br/index.php/desterro/article/view/8343/9480

Herrington, J., Oliver, R., & Reeves, T. C. (2010). A guide to authentic E-learning. Routledge.

Lateef, F. (2010). Simulation-based learning: Just like the real thing. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock, 3(4), 348. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-2700.70743

MacNeill, S., Johnston, B., & Smyth, K. (2021, November 9). Paulo Freire, University Education and Post Pandemic Digital Praxis. Paulo Freire, University Education and Post Pandemic Digital Praxis

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation (1st ed). Oxford University Press, Incorporated.

Nonaka, I., & Von Krogh, G. (2009). Perspective—Tacit Knowledge and Knowledge Conversion: Controversy and Advancement in Organizational Knowledge Creation Theory. Organization Science, 20(3), 635–652. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0412

Salas, E., Wildman, J. L., & Piccolo, R. F. (2009). Using Simulation-Based Training to Enhance Management Education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 8(4), 559–573. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.8.4.zqr559

Suhonen, S., Kankaanpää, R., & Kivimäki, M. (2025). Yhteiskehittämisen työpaja 1—Raportti (Konepaja-akatemia 2.0, p. 11) [Workshop report]. Tampereen ammattikorkeakoulu (TAMK) & SASKY koulutuskuntayhtymä. https://projects.tuni.fi/konepajaakatemia/julkaisut/

Teknologiateollisuus ry. (2024, September 2). Ammatillisen osaamisen on vastattava työelämän tarpeisiin [Organization]. Teknologiateollisuus. https://teknologiateollisuus.fi/tavoitteemme/osaava-tyovoima/ammatillinen-osaaminen/

Authors

Pauliina Paukkala works as a pedagogical specialist at Tampere University of Applied Sciences. Her expertise includes co-creation methods, simulation-based learning, and vocational teacher training, particularly in engineering education.

Matti Kivimäki is a senior lecturer at Tampere University of Applied Sciences with a background in industrial engineering and over 25 years of teaching experience. His interests focus on tacit knowledge transfer, learning process design, and the development of authentic technical training environments.

Photo: Freepik